BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://journal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-6165-en.html

, Hossein Rahimi1

, Hossein Rahimi1

, Nasim Mehrpooya2

, Nasim Mehrpooya2

, Seyyed Abolfazl Vagharseyyedin *3

, Seyyed Abolfazl Vagharseyyedin *3

, Sayyed Gholamreza Mortazavi Moghaddam4

, Sayyed Gholamreza Mortazavi Moghaddam4

2- Dept. of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Neyshaboor University of Medical Sciences, Neyshaboor, Iran.

3- Dept. of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran ,

4- Dept. of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran.

✅ Multidisciplinary supportive program is effective in reducing CB among the family caregivers of patients with advanced COPD.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is currently the fourth leading cause of mortality in the world and is estimated to become the third leading cause of death by 2030 (1). Its prevalence in Iran is 6.4% among men and 3.9% among women (2). COPD is associated with considerable economic burden including direct costs of using healthcare resources and indirect costs of lost productivity (3).

Like many other chronic diseases, most patients with COPD live in the community, hence receive care from informal caregivers including family caregivers, on a daily basis (4, 5). Caregiving of COPD patients can be a stressful experience for the family and may cause different challenges (6, 7). The progression of COPD progressively undermines patients’ functional abilities, making them more dependent on their family caregivers’ help and support (8). Such growing dependence increases family caregivers’ daily responsibilities and reduces their social activities. It may even negatively affect their health and cause them problems such as fatigue, depression, anxiety and fear (8-11). Moreover, when patients are hospitalized during the acute courses of COPD, their family caregivers experience fear and anxiety over their death (12, 13).

Caregivers’ response and reaction to caregiving-associated problems are conceptualized as caregiver burden (CB). CB is a multidimensional response to physical, psychosocial and financial stressors which is associated with caregiving experience (14). Most previous studies reported heavy CB among the family caregivers of patients with COPD (9, 15, 16). Heavy CB can cause depression and anxiety for caregivers, negatively affects their mental health, (17, 18) and thereby undermines their caregiving ability.

Heavy CB leaves caregivers in need of strong support. Studies on family caregivers of COPD patients show, that they need information about COPD and its treatments. They also require emotional support, practical help (for example to do household activities), access to peers and their support, professional help, nursing and medical advice and information about the future of their patients (6, 19, 20). Despite the wide range of the needs of COPD patients’ family caregivers, only a few interventional studies have been conducted to address their needs (15).

Given the wide variety of family caregivers’ needs, multidisciplinary interventions are needed for their fulfillment since they employ different professionals’ expertise. Two previous multidisciplinary supportive interventions for the family caregivers of patients with chronic conditions have shown that these interventions are effective to reduce CB and depression. It improves the families’ awareness of their needs (21, 22). Yet, to the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies on the effects of multidisciplinary interventions have addressed the CB of the COPD patients’ family caregivers. Therefore, the present study was conducted to narrow this gap. The purpose of the study was to assess the effects of a multidisciplinary supportive program on CB among the family caregivers of patients with advanced COPD.

Participants’ CB was assessed using Zarit Burden Interview. Its 22 items have been scored on a five-point scale from 0 (“Never”) to 4 (“Always), resulting in a total score of 0–88 with higher scores indicating greater CB (14). It has been one of the commonly used instruments for CB assessment among the family caregivers of patients with COPD in the previous studies (17). Participants completed this scale before random allocation to the study groups, as well as immediately and two months after the study intervention.

For reliability assessment in the present study, 50 eligible caregivers completed the scale and its Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to be 0.81.

Intervention

Study intervention was a multidisciplinary supportive program which was implemented for participants in the intervention group in three main phases. In the first phase, 36-minute educational group sessions were held every other day, by a pulmonary disease specialist (two sessions) and an experienced nurse in COPD care (one session).

Educations were provided through lectures and group discussions. Educations provided by the pulmonary disease specialist were about COPD and its pathology, symptoms, risk factors, aggravating factors, medications and medication side effects. Provided educations by the nurse (the first author) were about smoking cessation, healthy diet, physical activity and available support systems for COPD patients (including the National Welfare Organization and social workers in hospital settings). At the end of each session, a printed pamphlet was provided to each participant which contained the same provided materials in that session.

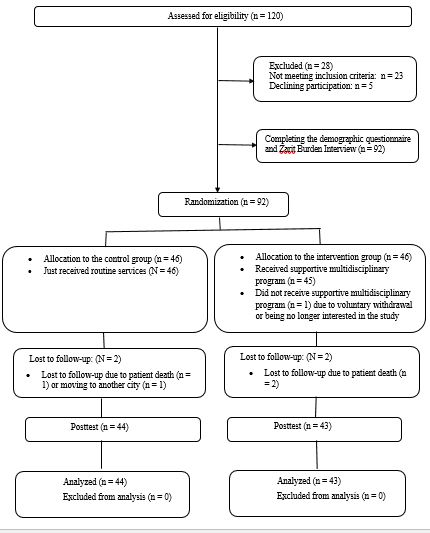

Figure 1. The CONSORT diagram of the study

In the second phase, participants in the intervention group were divided into two 23-person groups; participants of each group were provided with 26-minute educational sessions about mental health and the role of coping strategies in mental health maintenance. These two sessions were held by a psychiatric nurse. In the third phase, the participants were divided levels into four groups according to their educational: each including 11 or 12 people. All participants attended in three 1.5-hour weekly peer support sessions.

Initially, a leader was selected for two groups by an attending physician. An experienced instructor in peer support education, provided the leader the educations about the goals of peer support sessions, management of group discussions in the sessions and preventing the deviation of group discussions from the goals in two sessions. Then, under the leadership of this leader, participants shared their experiences about caregiving to their patients in peer support sessions. Participants in the control group received routine care services which consisted of patient education by their physicians and nurses and a series of COPD-related educational pamphlets.Data Analysis

SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL., USA) was used for data analysis. With respect to the participants’ and patients’ personal characteristics, between-group comparisons were performed through the independent-sample t test, Chi-square and the Fisher’s exact tests. Between- and within-group comparisons for the mean score of CB were done using independent-sample t test and repeated-measure analysis of variance, respectively. Bonferroni’s test was used for the post hoc analysis of the results of the repeated-measure analysis of variance. The independent-sample t test and the Mann-Whitney U test were also used to compare the groups, respecting the amount of changes in the mean score of CB.

Ethical Considerations

This study has the approval of the Ethics Committee of Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran (code: IR.BUMS.REC.1397.360). Participants were informed about the study aims and confidential handling of the study data. Also, a written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Final data analysis was conducted on the data which were collected from 43 participants in the intervention group, and 44 in the control group (Figure 1).The mean age of participants in the intervention and the control groups was 38.74±13.73 and 42.16±15.71, respectively (P>0.05). Also, the mean age of patients was 63.65±13.21 years in the intervention group, and 64.50±16.02 years in the control group (P>0.05). The duration of COPD in the intervention and the control groups was 6.65±4.25 and 6.03±3.81 years, respectively. Groups did not significantly differ from each other respecting participants’ and their patients’ characteristics (P>0.05, Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1. Caregivers' characteristics

| Group Characteristics |

Caregivers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | P value | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Gender | Female | 23 (53.5) | 29 (65.9) | 0.24* |

| Male | 20 (46.5) | 15 (34.1) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 6 (14) | 5 (11.4) | 0.72* |

| Married | 37 (86) | 39 (88.6) | ||

| Occupation | Employee | 4 (9.3) | 5 (11.4) | 0.43** |

| Self-employed | 9 (20.9) | 5 (11.4) | ||

| Laborer | 9 (20.9) | 5 (11.4) | ||

| Housewife | 18 (41.9) | 26 (59.1) | ||

| Retired | 3 (6.8) | 3 (6.8) | ||

| Educational level | Primary | 12 (27.9) | 14 (31.8) | 0. 6* |

| Secondary | 24 (55.8) | 20 (45.5) | ||

| Tertiary | 7 (16.3) | 10 (22.7) | ||

| Kinship with patient | Parent or sibling | 7 (16.3) | 10 (22.7) | 0.1* |

| Spouse | 4 (9.3) | 10 (22.7) | ||

| Daughter | 14 (32.6) | 13 (29.5) | ||

| Son | 11 (25.6) | 10 (22.7) | ||

| Others | 7 (16.3) | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Place of residence | Urban areas | 24 (55.8) | 26 (59.1) | 0.76* |

| Rural areas | 19 (44.2) | 18 (40.9) | ||

| *: The results of the chi-square test; **: The results of the Fisher’s exact tests | ||||

Table 2. Patients’ characteristics

| Group Characteristics |

Patients | |||

| Intervention | Control | P value | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Gender | Female | 22 (51.2) | 21 (47.7) | 0.75* |

| Male | 21 (48.8) | 23 (52.3) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 1.00* |

| Married | 43 (100) | 43 (97.7) | ||

| Occupation | Employee | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0.43** |

| Self-employed | 7 (16.3) | 6 (13.6) | ||

| Laborer | 13 (30.2) | 11 (25) | ||

| Housewife | 21 (48.8) | 20 (45.5) | ||

| Retired | 1 (2.3) | 6 (13.6) | ||

| Educational level | Illiterate | 18 (40.9) | 18 (40.9) | 0.76** |

| Primary | 21 (48.8) | 22 (50) | ||

| Secondary | 4 (9.4) | 3 (6.8) | ||

| Tertiary | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Place of residence | Urban areas | 21 (48.8) | 20 (45.5) | 0.75* |

| Rural areas | 22 (51.2) | 24 (54.5) | ||

Moreover, although there was no statistically significant difference between the groups respecting the mean score of CB at the first posttest (P=0.66), the mean score of CB was significantly less in the intervention group compared to the control group, at the second posttest (P=0.007, Table 3).

| Time Group |

Before | Immediately after | Two months after | Test results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean± SD | Mean± SD | Mean± SD | F |

p |

||

| Intervention | 34.02 ± 14.71 | 32.55 ± 13.57 | 27.53 ± 7.77 | 10.57 | 0.01* | |

| Control | 32.95 ± 13.30 | 33.77 ± 12.24 | 33.41 ± 11.64 | 0.34 | 0.63* | |

| Test results | t | 0.36 | 0.44 | 2.76 | __ | __ |

| p | 0.72** | 0.66** | 0.007** | __ | __ | |

| *: The results of the repeated measures ANOVA; **: The results of the independent-sample t test | ||||||

Table 4. Between-group comparisons respecting the pretest-posttest mean differences of the mean score of CB

| Group Time |

Intervention | Control | Test results | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | t or z | p | |

| Baseline and first posttest | –1.47 ± 7.39 | 0.81 ± 6.19 | 1.46 | 0.14* |

| Baseline and second posttest | 6.49 ± 13.72 | 0.45 ± 8.01 | 2.89 | 0.005** |

| First and second posttests | 5.02± 11.28 | 0.36± 5.35 | 2.47 | 0.02** |

| *: The results of the Mann-Whitney U test; **: The results of the independent-sample t test | ||||

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the effects of a multidisciplinary supportive program on CB among the family caregivers of patients with advanced COPD. The total mean score of CB was 33.48±19.94 among all 87 participants. This value is different from the values which have been reported in some previous studies. For instance, in a study the mean score of CB among the caregivers of patients with COPD was reported to be 40.91±20.58 (24). An explanation for this difference may be the fact that participants were the caregivers of hospitalized patients in clinical settings; they had greater CB values compared to our participants whose patients referred to an outpatient clinic.

Moreover, the present study was conducted in the collectivistic culture of Iran, where most family members of COPD patients are among the main sources of social support for their patients (25) and the main family caregivers of patients may experience lower CB compared to the caregivers in non-collectivistic cultures.

Study findings also revealed that the mean score of CB significantly decreased in the intervention group across the three measurement time points. The significant effects of the study intervention may be attributed to its different components. In the first component of the intervention, a pulmonary disease specialist provided informational support to caregivers. They need professional support in order to provide more appropriate care for their patients (26). The need for information about strategies to support their patients and the need for support to manage their care-related roles are among their common important supportive needs (27, 28).

A study about the common needs of the caregivers of COPD patients showed that more than half of them needed information about the future of their patients; one third of caregivers needed information about COPD, and most of them needed professional support to manage their patients’ problems and their own feelings and concerns (29).

The second component of the study intervention was education about coping strategies. Former study found that providing education about problem-focused coping strategies significantly reduced CB among the caregivers of patients receiving hemodialysis (30). Therefore, education about coping strategies in the present study might have contributed to the significant decrease in caregivers’ CB.

The third component of the study intervention was peer support. Former studies reported contradictory results about the effects of peer support on CB among the caregivers of patients with chronic conditions. For instance, according to the reported results of a study, peer support did not significantly affect CB among the caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (31). Another study reported its effectiveness to significantly reduce CB among Alzheimer’s disease caregivers (32).

Peer support is a type of social support, which has four main aspects including emotional, instrumental, information and appraisal support. Emotional support includes showing empathy and love and compassion, while instrumental support refers to tangible help. Informational support is defined by the provision of recommendations and information. Appraisal support is the communication of useful information for self-evaluation (33). Social support can facilitate the expression of experiences and concerns which reduces negative psychological responses and emotions (34).

Our findings showed a slight insignificant increase in the mean score of CB in the control group. This increase is attributable to the growing dependence of patients on their caregivers, due to the deterioration of their conditions over the time (8).

We did not find any significant differences between-group, respecting the mean score of CB at the first posttest. At the baseline, the mean score of CB in the intervention group was slightly greater than the control group; at the first posttest, it was slightly less in the intervention group compared to the control group. According to the mean score of CB at the second posttest, these findings denoted that adequate amount of time is needed to observe the positive effects of multidisciplinary supportive program on CB.

Conclusion

This study suggests that a multidisciplinary supportive program is effective in significantly reducing CB among the caregivers of COPD patients and it can be useful to reduce CB among the cited caregivers.

Acknowledgements

This study is based on research project No. 455746, which was approved by Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Received: 2020/08/12 | Accepted: 2020/12/19 | Published: 2021/02/28

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |